If you're looking to build a thick, powerful back, the barbell row is your golden ticket—but chances are, you're butchering the movement without even realizing it. This classic lift is a staple in strength training for a reason: it targets your lats, traps, rhomboids, and even your biceps and forearms, making it one of the most effective compound exercises out there. But here’s the kicker—most people mess it up by sacrificing form for ego-lifting weight, turning what should be a back-building powerhouse into a lower-back wrecking ball. Let’s break down how to do it right so you can stop spinning your wheels and start packing on serious muscle.

Before you even think about loading up the bar, nail your setup. Stand with your feet shoulder-width apart, knees slightly bent, and grip the bar just outside your legs with an overhand grip. Hinge at your hips—not your waist—until your torso is nearly parallel to the floor. Your back should be flat, not rounded, and your chest should be proud like you’re trying to show off a medal. This position keeps your spine safe and ensures your back muscles, not your lower back, do the heavy lifting. If you’re feeling tension in your hamstrings, good—that means you’re hinging correctly. Now, brace your core like someone’s about to punch you in the gut. This isn’t just about looking cool; it’s about protecting your spine and maximizing power transfer.

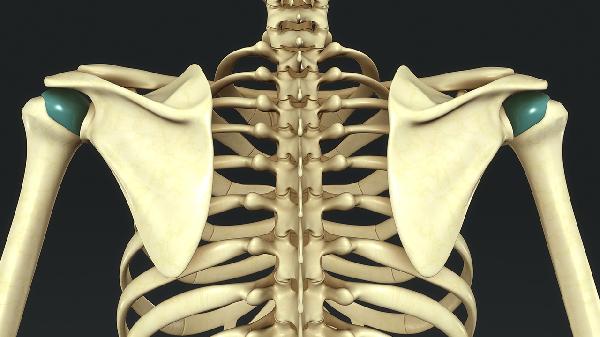

Here’s where most folks go wrong—they yank the bar off the floor like they’re attempting a deadlift PR. Newsflash: the barbell row isn’t a deadlift. The movement starts with your elbows driving back, not your hips rising. Think of pulling the bar toward your belly button, not your chest. Your elbows should skim your sides as you squeeze your shoulder blades together at the top. If the bar’s banging against your ribs, you’re probably using too much momentum and not enough muscle. And for the love of gains, don’t let your shoulders shrug up to your ears—keep them down and back to keep the focus on your lats. The bar should travel in a straight line; if it’s looping around like a rollercoaster, you’re doing it wrong.

Let’s address the elephant in the gym: ego lifting. Just because you can row 315 pounds doesn’t mean you should—especially if your form looks like a question mark. The barbell row isn’t about impressing the person next to you; it’s about controlled tension on your back muscles. Start with a weight that allows you to pause for a second at the top of each rep, squeezing your back like you’re trying to crack a walnut between your shoulder blades. If you’re swinging or using your hips to cheat the weight up, it’s too heavy. On the flip side, if you’re cranking out 20 reps with zero burn, it’s too light. Find the sweet spot where the last few reps of each set feel challenging but not impossible.

Besides the usual suspects—rounding your back or using too much weight—there are a few sneaky mistakes that can sabotage your rows. First, letting the bar drift away from your body turns the exercise into a reverse fly, taking the emphasis off your lats. Keep the bar close, almost like you’re dragging it up your thighs. Second, failing to control the eccentric (lowering phase) is a missed opportunity. Lower the bar slowly—about twice as long as it took to pull it up—to maximize muscle damage (the good kind) and growth. And third, rushing through reps like you’re late for dinner. Each rep should be deliberate. If you can’t feel your back working, you’re moving too fast or using too much momentum.

Once you’ve mastered the standard barbell row, try these tweaks to keep your back guessing. The Pendlay row—named after weightlifting coach Glenn Pendlay—involves pulling the bar explosively from a dead stop on the floor each rep. This eliminates momentum and forces pure strength. The Yates row, popularized by bodybuilder Dorian Yates, uses a more upright torso and underhand grip to target the lower lats and biceps. And if you’re feeling adventurous, the chest-supported row (using an incline bench) removes lower-back involvement entirely, letting you hammer your upper back without worrying about form breakdown. Each variation has its place, so rotate them into your program to avoid plateaus.

Since the barbell row is a compound movement, it deserves a prime spot in your routine—not some afterthought tacked on at the end. Aim for 2-3 heavy rowing sessions per week, alternating between variations to prevent overuse injuries. If you’re prioritizing back growth, consider starting your workout with rows instead of saving them for later when you’re already fatigued. Sets and reps can vary, but a good starting point is 3-4 sets of 6-10 reps with a weight that challenges you without compromising form. And don’t forget to pair rows with vertical pulling (like pull-ups) to hit your back from all angles. A balanced back is a strong back.

At the end of the day, the barbell row is a beast of an exercise—but only if you do it right. Ditch the ego, focus on form, and watch your back transform from “meh” to “massive.” Your future self (and your deadlift PR) will thank you.